Why Doesn't the U.S. Have an Industrial Development Bank?

I'm in a book club dedicated to manufacturing books. It's run by Eric Vallieres on X (Twitter). We had our first meeting in October. Some highlights from the conversation:

- Defense contracting sustains the industrial base, but it also kills innovation because companies maintain contracts for decades and don't innovate

- The Trump admin's current ever-shifting tariff bargaining strategy isn't a sound base for planning or investment. We hope tariff policy settles into more predictability

- American manufacturing / industrial companies tend to want to pad their margins through price negotiation. This leads to a lot of friction in the buying / selling process. The Chinese sell fast and cheap. It can takes weeks to get a quote from an American company while a Chinese company will communicate 24/7 on Whatsapp and quote right away. A lot of time is wasted this way

- A lot of potential new industrial ventures are caught in the American capital formation trap. They don't have the cash flows to be underwritten by banks, and don't offer returns that would make them attractive enough for VC

More on this last point in a minute, but first you should DM Eric Vallieres on X if you'd like to join the Manufacturing Book Club.

Manufacturing Book Club Book #1:

— Eric Vallieres (@EricVallieres84) September 12, 2025

Made in the USA: The Rise and Retreat of American Manufacturing by Vacal Smil

Tentative date for the first meeting is Thursday October 23rd at 8:00PM EST hosted on X Spaces

Available in paperback, hardcover, e-book (kindle) as well as… https://t.co/tvZftjtgf0 pic.twitter.com/GOJevRUzbp

The Industrial Capital Valley of Death

A big problem with planning to just go open a new widget factory in the United States is that you'll have a hard time raising capital:

- Banks want to underwrite businesses with stable cash flows

- Industrial PE prefers companies with fully depreciated assets

- Returns aren't attractive enough for VC

How did other countries help new companies solve this funding gap? After all, Western Europe, Japan, Korea, and China (and many other countries) industrialized pretty hard after WW2. We can draw some inspiration.

Spain Built a Sea of Plastic, Then It Got Rich

I was watching this youtube video about how one region of Spain built 370 square kilometers (142 sq miles) of greenhouses and turned one of the driest regions in Spain into the center of a $3.7 B / year agriculture industry. The economics work really well because the greenhouses in hot / dry Alméria don't need to be heated and use 22 times less energy than greenhouses heated by natural gas. Growers in the region can export high quality fruits and vegetables in the winter at a fraction of the cost compared to greenhouse operations in colder climates. As a result, Spanish products from Alméria supply grocery stores all over Europe.

It seems like a sub-plot, but one of the most interesting thing about this video is the Cajamar research station. It's actually an agricultural laboratory and educational institution, and it's part of a local cooperative of more than thirty rural banks. The banks have deep experience underwriting agricultural projects; they use capital from other regions to fund farmers building new greenhouse farms in Alméria. They use the R&D facility to discover growing techniques and validate their economic viability, then they provide farmers with vital training needed to manage technically complex growing operations, thereby de-risking the bank loans. It's an eminently virtuous cycle, and the Cajamar fund / train model succeeded in transforming one of Spain's poorest and least productive agricultural geographies into the richest and most technically advanced. Considering the specialized knowledge needed to run the farms profitably, it really couldn't have been done otherwise.

Wouldn't it be great if we had banks like this in the United States?

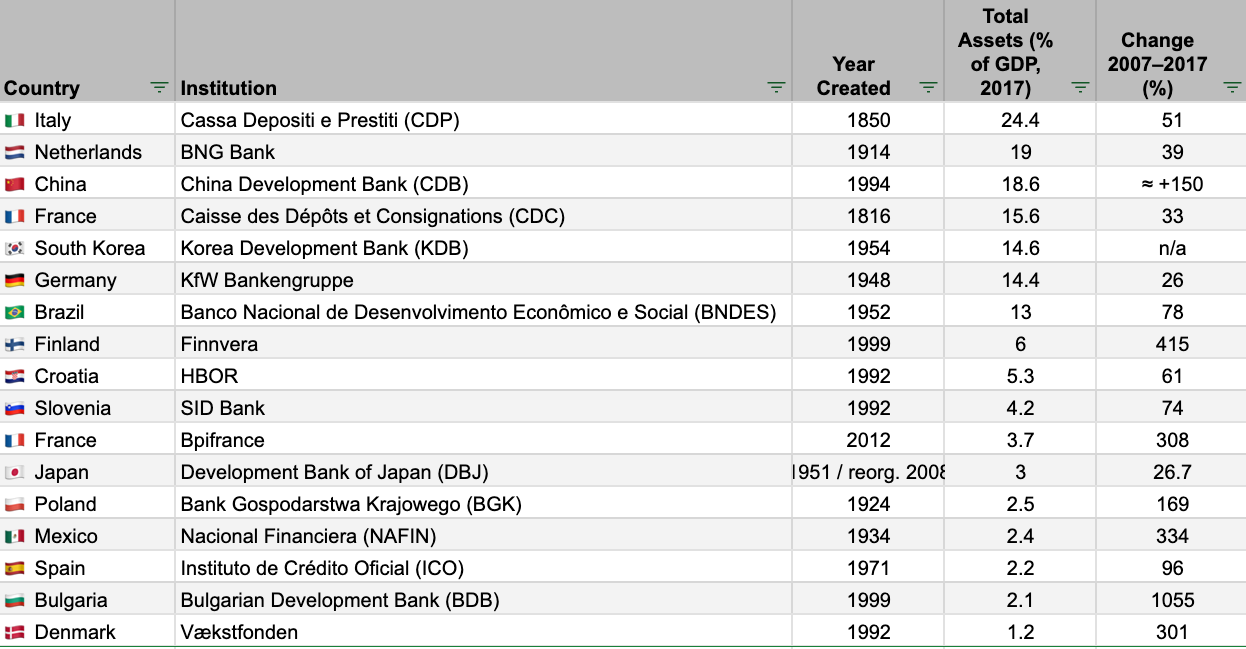

The Cajamar example is not unique. In fact, it's just an example of a small subset of a financial system overseen by a national development bank. Every advanced industrialized nation in the world has a development bank. The largest is China's, whose loan book is capitalized at $2.7 trillion.

Significant Development Banks Worldwide:

A typical development bank has the following features:

Capital & Funding Structure

- Public ownership: Usually state-owned (national treasury, finance ministry, or sovereign fund as majority shareholder).

- Long-term capitalization: Paid-in capital from the state plus retained earnings; often backed by an explicit or implicit sovereign guarantee.

- Bond issuance: Raises bulk of funds by issuing long-term bonds (often tax-favored or guaranteed) in domestic and international markets.

- Preferential funding costs: Because of sovereign credit, NDBs borrow at near-sovereign rates and on-lend more cheaply to development projects.

- Multilateral lines: May borrow from or co-finance with the EIB, World Bank, ADB, etc.

Mandate & Objectives

- Developmental rather than commercial: Focused on economic transformation, not profit maximization—though expected to remain financially sustainable.

- Strategic priorities:

- Industrial modernization & SME support

- Infrastructure (transport, energy, digital)

- Innovation, R&D, and green transition

- Export or regional integration

- Counter-cyclical role: Expands lending during recessions or credit crunches to stabilize investment.

- Policy alignment: Executes parts of national or regional industrial, environmental, and social policy.

Operational Model & Cooperation

- “On-lending” model: Works through commercial or cooperative banks, which originate loans to end clients while the NDB provides wholesale funding or guarantees (e.g., KfW’s Hausbank system, ICO in Spain).

- Direct lending: For large infrastructure or strategic corporate projects.

- Guarantees and risk sharing: Offers credit guarantees, mezzanine finance, or first-loss tranches to crowd in private banks.

- Advisory & technical assistance: Provides project preparation, training, and capacity building—especially for SMEs or municipalities.

- Public-private co-financing: Partners with institutional investors, export-credit agencies, and private funds for blended finance.

Instruments & Products

- Long-term loans (often 5–30 years) at below-market or fixed rates.

- Credit guarantees to lower risk for local banks.

- Equity & venture capital windows (e.g., Bpifrance, Finnvera).

- Securitization & bond programs for infrastructure and green projects.

- Green / social bonds—increasingly used to fund climate and inclusion goals.

Governance & Safeguards

- Public mandate, commercial discipline: independent management under government policy guidance.

- Performance metrics: financial sustainability + developmental impact.

- State audit & parliamentary oversight ensure accountability.

Systemic Role

- Market maker for “patient capital.”

- Catalyst for private finance: by taking early or subordinated risk.

- Bridge between government strategy and private enterprise.

- Knowledge hub: collects sector data, publishes studies, and disseminates best practices to local banks and firms.

In short: a development bank is a state-backed, long-term financial engine that supplies the kind of credit, risk tolerance, and technical know-how that commercial finance alone cannot—especially for industrialization, infrastructure, and innovation.

While industrialization in the United States and Britain proceeded more or less as a laissez-faire phenomenon, most of the rest of the world developed their industrial economies through a process involving significant state guidance and intervention. In each case, development banks each played a major role in their respective country's industrialization efforts, whether it was western European nations rebuilding after WWII, or Asian countries driving development in the 70's and 80's. We should acknowledge that these efforts were successful: the combined manufacturing output of as a share of GDP for all the countries listed on the table is around $10 trillion in 2017 dollars, about 4x the manufacturing output of the United States. Clearly in the latter half of the 20th century there was an effective playbook for industrialization, a key component of which was the state-directed financial institution, aka the development bank.

What might an American development bank look like?

If the United States government committed seriously to reindustrialization, let's imagine what the American Development Bank would look like.

- Capitalization target of 10% of GDP (well below the 15-20% capitalization range of Germany / Italy / China / Korea) gives us a balance sheet of $2.8 trillion, on par with China

- Funded by $2.5 trillion in Long Term U.S. Development Bonds, as well as paid in equity from the U.S. Treasury, for a 10% equity ratio

- Governed as a private corporation chartered and overseen by Congress

- Mandate focused on industry, energy renewal, supply chain, infrastructure, and industrial innovation

- Meets the need for "missing middle" financing needed for launching long-term manufacturing-focused projects

- Partners with commercial banks, industry-focused credit unions, and state development corporations. Direct investment could be executed by 12 regional ADBs, similar to the structure of the Federal Reserve

- Can issue $250-300 billion of new investment per year, about 1% of GDP

- When paired alongside private capital (co-investment), could catalyze $1 trillion / year in new investment

A U.S. Development Bank funded at 10 % of GDP would be a $2.8 trillion national investment engine—large enough to reshape American manufacturing, energy, and infrastructure capacity, yet still fiscally manageable (comparable to a single QE tranche). It would put the U.S. on roughly the same industrial-finance footing as Germany, Italy, and China.

A bank of this type would be similar in size and structure to the U.S. Federal Reserve, but for industry. Just like how the Federal Reserve provided the stability and financial infrastructure for the rise of the American banking sector, the American Development Bank would provide the framework for long term guidance and large scale investment in the (re) emergence of the American industrial economy. The bank could help launch thousands of factories, generate trillions of dollars in manufacturing / trade activity, and put millions of Americans back to work. In an age when 60% of new college graduates can't find work, something like this, if done properly, could quite literally save the U.S. economy.

Why don't we already have a development bank?

A few reasons:

- The U.S. has already enjoyed the world's largest and most developed private capital markets for over a century; for most of our industrial history there was little need for public finance

- Since the 1950's the U.S. has been committed to free trade policies in an effort to help develop the economies of allies / trading partners. A state-directed development bank would have conflicted with this strategy

- Previous state-directed finance efforts in the U.S. have been marred by accusations of crony capitalism and inefficient capital allocation (Reconstruction Finance Corporation / Solyndra scandal etc.)

Let's discuss these problems. In the first case, despite the scale of sophistication of our private capital markets, there's clearly a need for "missing-middle" finance. This is evident from ground-level discussions with would-be founders who face steep challenges with capital formation. Somewhere in the last few decades private banks have lost the appetite or the capability to invest in new manufacturing. A small example: Manufacturers and Traders Trust Company, now known as M&T Bank, was founded in 1856 in Buffalo to meet the financial needs of the growing manufacturing and railroad industries in that region. Today, manufacturing loans account for 3% of M&T's balance sheet. It's no surprise that when your industry is shipped overseas, even your banks forget how to underwrite industry. Development banks provide a proven model for jump-starting national industrial finance.

With regards to international trade, the political climate in the United States has shifted decisively in favor of greater autonomy. And it's not just President Trump and the disaffected Rust Belt who are in favor of reshoring and curtailing free trade: the COVID pandemic revealed to every manufacturer in America just how fragile our supply chains are. At the same time, between PPP, the CHIPS act, and the Trump admin's direct investment in Intel, both Democrats and Republicans alike are demonstrating a greater willingness to exercise government muscle in pursuit of specific economic goals. Now is the right moment to consider a development bank.

Finally, there's going to be bi-partisan support for reindustrialization. If you read Peter Zeihan, there's reason to believe that there are structural forces at play in the coming decades that will interrupt trade and force many countries, including the United States, to reshore industries whether we want to or not. We're just now seeing the opening rounds of a future where easy trade is less certain, and where political constituents demand economic opportunity. Smart politicians are already getting behind this. The Reindustrialize conference in July was attended by an impressive contingent of Congressional Senators and Representatives from both sides of the aisle, one of the few policy areas where I've seen bipartisan enthusiasm for anything in today's politicized climate. It's hard to get Congress to agree, but it seems they agree on getting America back to work. Obviously an American Development Bank would be a massive political undertaking, but as imperatives for industrialization intensify, so will the willingness to consider novel solutions. If we're serious about reindustrializing, why not a development bank?

I intended this little article to be a short introduction to the idea of development banks for my American audience, and to float a thought experiment about what an American Development Bank might look like. Obviously there's much more relevant literature out there to read, and I'm sure there are professionals out there who have been immersed in this subject for years. If you would like to discuss further, or know anyone who is working on proposals related to a U.S. development bank, please get in touch: rich at blackpowder.io