Leaders, Charlemagne, and Fractal Culture

"Soldiers are the same everywhere, but leaders make them differentiated. Leaders make the difference."

As a lieutenant in the Army, I once saw a new CO take command of the worst company in the battalion. He renamed them "Tiger Company." He had the company buildings repainted inside and out. He ordered Crossfit equipment and had it installed in the company bays. He put leaderboards on the wall to record high scores for physical challenges. Then he got to work re-training the company from the ground up. They arrived earlier, ran farther, worked harder, and left later than anyone else. Within three months they were the top scoring company in the entire brigade. Not just in PT but by every measurable metric. He totally transformed them.

Through my business experience and reading I've seen this interesting dynamic consistently. Leadership isn't just effective decision-making. Effective leaders transmit their vision by physically modeling it, both in their personal engagement and in the work patterns and artifacts that make up their workplace.

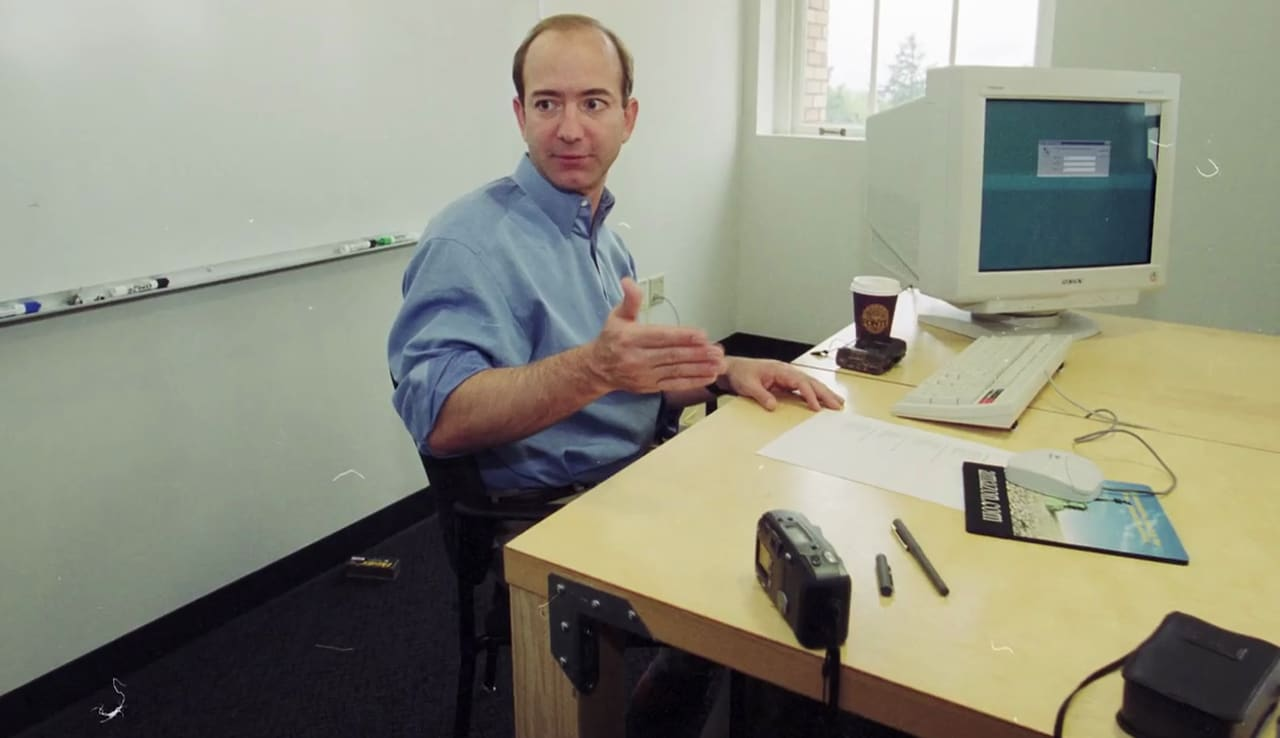

For example, for a long period in Amazon's early history, Jeff Bezos insisted that the team use desks made with doors from Home Depot. It seems nonsensical. Amazon raised millions of dollars. They could afford real desks. But Bezos wanted to send a message. Amazon would be so maniacal about delivering savings for the customer that they would eliminate unnecessary costs anywhere they could be found, even including their personal desks. To this day Amazon regularly presents a "Door Desk Award" featuring a tiny model door desk to celebrate employees who save significant costs within the company.

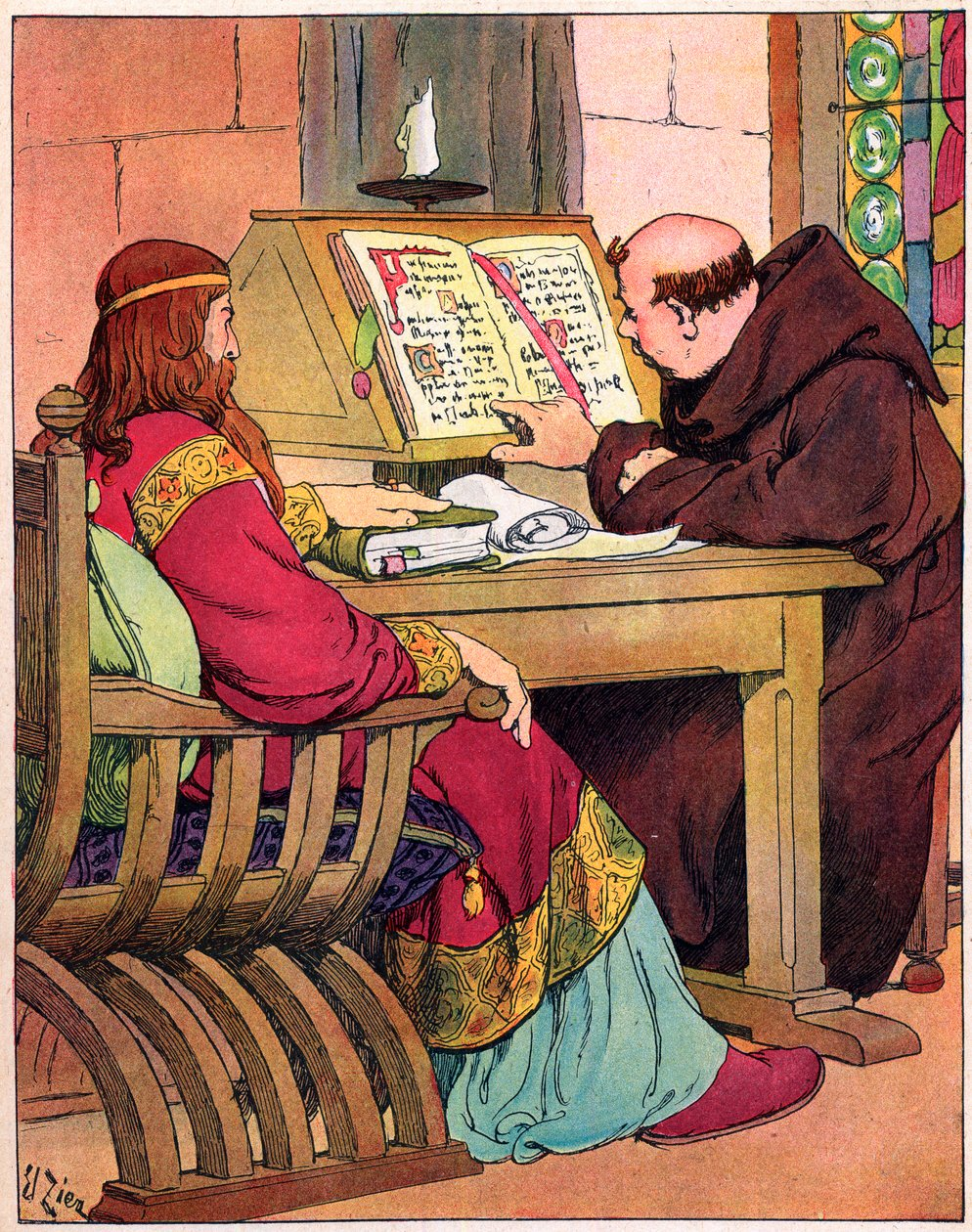

To give an example from history, consider the court of Charlemagne in the middle of the Dark Ages. Probably no greater leadership challenge could ever exist: warring nobles, a weak central state, ubiquitous illiteracy and poor record keeping. Amidst this Charlemagne's court was a model of order. He lived life in the saddle and traveled everywhere with his entourage. He began and ended each day with simple meals, prayer, and vigorous exercise. Although he was semi-literate and never quite mastered the art of writing, he was keenly aware of the value of the written word and had a continuous rotation of scribes who would read aloud all kinds of literature to him constantly. These reading sessions weren't only for his benefit; he expected visitors to listen with him and be able to discuss the texts at length. When he visited towns he would immediately fix glaring issues. He adjudicated disputes, sponsored public works, and castigated priests for having dirty churches. Like most great leaders, Charlemagne seemed to know that culture is made from the sum of many seemingly inconsequential details. He expected the nobles he charged with ruling the far-flung regions of his kingdom to adopt his interests and priorities, and these were modeled personally in the way he lived his life and organized the immediate world around him.

But why should door desks and dirty church vestments matter? Surely in the age of remote work and genius Silicon Valley coders who walk the cafeteria barefoot, the only thing that matters is results. You would think that in today's world the aesthetic trappings of the traditional workplace would recede in importance. Why are "inconsequential details" so important?

The answer lies in our human nature. Despite all our abstracted patterns of competence we are still physical beings. We are shaped and influenced by the world around us, and the complex of details that surround us in our work communicate more deeply and consistently than the spoken and written word. Psychologists call this effect "enclothed cognition." Clothing and physical artifacts carry symbolic and functional meaning that act as cognitive cues. When the scientist arrives at the lab on a Monday he puts on a lab coat, and the ritual clears away the mental fog of the weekend. When we see the sales numbers on a prominent place on the office whiteboard we are unconsciously reminded of our primary goal for the day. The door desk reminds us that we're in a scrappy organization every time we sit down at it. I don't see these markers as cynical psychological tricks: they're deep acknowledgements of our human nature that enrich and add meaning to our daily lives.

The French thinker René Girard proposed that human desire is mimetic. That is, most desires do not arrive spontaneously, but are imitations of the desires we see in other people. Anyone who has observed young children at play understands the phenomenon when one child suddenly cries for a previously forgotten toy simply because another began playing with it again. Girard's simple observation also elegantly bridges philosophy with market dynamics: as business thinkers we intimately understand that the higher the demand for an item, the higher the price.

With these two ideas (enclothed cognition / mimetic desire) we can see how small details relate to leadership. Culture comes from leaders, and when leaders emphasize the small details that make the markers of company culture, it serves as an expensive signal that those things and their symbolic meaning are important. The leader is saying "I desire this." This inspires mimesis when people on the team perceive the leader's desire and imitate it by adopting the symbols, beliefs, and behaviors that underlie that desire. The leader's behavioral and symbolic complex is a fractal of culture that propagates through the whole organization.

This is why details matter. Effective cultures take many different forms. It's not about mere decoration. You're just as apt to find competence in a highly polished black-shoe law firm as you are at a scrappy barebones startup. The one thing they have in common is that effective organizations are led by leaders who have a strong vision for culture and are willing to invest their personal desire and attention into those details that create the cultural context that communicates and reinforces cultural norms. Competence is an aesthetic complex that we participate in.

As business leaders we should never be afraid to think deeply about the details and emphasize them wherever we can. Small things matter. The right detail invested with symbolic meaning carries weight far beyond what it may appear to on the surface.

PS: I use the term "Dark Ages" for the sake of legibility and rhetorical effect. I know that historians now generally prefer to use the term "Early Middle Ages" for the period in Europe from 500-1000 AD.