War, Business Strategy, and Kerbal Space Program

When I left the my career as an Army officer in 2015, I had a deep understanding of strategy in a military context:

In war, strategy is the application of your strength against an enemy's weakness in order to degrade the enemy's ability and will to fight.

However, as I transitioned into private sector business, I struggled to see how my experience could be translated into a business context. I had been trained since West Point to think of strategy in a Clausewitzian sense, that, while it does heavily emphasize the broader political context of conflicts, always assumes the existence of an adversary. There are key differences I couldn't overcome:

- In business, you don't act on your competition directly. You interact with them indirectly through the medium of the market.

- Even the idea of competition itself is suspect: the ideal business is one that has no competitors.

- In war, the terrain is bounded physical terrain, but in business, the market is conceptual, and effectively limitless

- In business, you may even cooperate with competition. In fact, a strategy of cooperating with competitors can be so advantageous that in many cases there are laws against it.

So I was left with the question: if the focus of action in business strategy is not the competitor, but the customer, what are the mechanisms that allow us to build strategic advantage in the market?

Theory of Strategy

During my MBA at IESE in Barcelona, I was exposed to Porter's Five Forces. For my non MBA, non-consultant friends, Porter's Five Forces is a framework developed by Michael Porter and first published in Harvard Business Review in 1979.

Porter argued that a company's strategic advantage is influenced by five fundamental market forces that affect that company's ability to capture value from its business activities:

For example, grocery stores operate in a very competitive market where consumers can easily find alternatives by simply driving a few blocks. Therefore, grocery stores are forced to offer lower prices. As a result, profit margins for grocery stores are typically very low, about 1-3%. One way that grocery stores can create strategic advantage for themselves is through scale, which gives them bargaining power over their suppliers. This is one of Walmart's key differentiators: because they are so large they are able to extract better deals and payment terms from their suppliers, allowing them to optimize their cash flow despite their low profitability.

On the other hand a business like Hermès operates in the luxury goods space, a completely different dynamic. These companies are differentiated by their branding; essentially their reputation and desirability in the minds of potential customers. Their brand is so strong and singular that threat of new entrants or substitutes is effectively nullified, and bargaining power of buyers is very low. Therefore, Hermès has pricing power and can charge an enormous premium for products like handbags. Hermès International has net profit margins in excess of 30%.

In business school these frameworks helped me understand that business strategy is more akin to counter-insurgency doctrine, where the center of gravity is the allegiance of the population (or the buying decision of the customer). The terrain is conceptual and completely flexible: the discovery of a new technology or under-served market segment, the gradual development of a brand identity, or even finding a novel use for an old product, could open (or close) a market. The domain of consideration is functionally infinite because market opportunity can be found anywhere.

However, I was still left with questions. Porter's Five Forces is a great framework, but how do you bridge the gap between theory and practice? One major problem for a practitioner is that when you begin to think seriously about strategy, you have to begin with your starting position, which is often zero: a new company or a business that has brought you on precisely because they have no strategy.

The theory was unsatisfying to me, because strategy should connect ideas to action.

The Practice of Strategy

I needed a working definition of business strategy, and I found it in Good Strategy Bad Strategy by Richard Rumelt. In the book, he emphasizes repeatedly how your view of the strategic landscape should be transformed into coordinated action.

For example, while the common wisdom was that a discount grocery store needed a population base of greater than 100,000, the management of Walmart understood that by innovating on the discount supermarket format, they could turn this wisdom on its head and operate profitably in much smaller towns. They implemented a series of elements that contributed to this strategy:

- Reduced personnel costs and higher inventory turnover by implementing open circulation, self-service, and cashier check-out (most grocery stores at the time kept goods behind a counter, requiring you to speak to a clerk to be served)

- A robust distribution network with computer reporting of inventory levels allowing for low inventory and just-in-time delivery to Wal Mart stores

- A highly centralized management system that offered better coordination across the Wal-Mart network, and lower overhead

The point is that any one of these elements would be insufficient to replicate Wal-Mart's success: they are all parts of a coordinated whole that allowed Wal-Mart to apply their strength (format innovation + logistics and admin efficiency) to a unique opportunity (small towns) that was being ignored by other big box discount grocery chains.

I began to see strategy implementation as something like building a vehicle. This is where Kerbal Space Program comes in.

If you're not into aerospace or pc games, I'll explain. Kerbal Space Program is a computer game where you build space ships to explore other planets. While the little green protagonists have a cute and cartoony aesthetic, the orbital mechanics that underlie the game are very realistic. This imposes some tough constraints on the way you build your spaceships. Each design has to be precisely adapted for its particular mission, or run the risk of failure, sometimes spectacular failure!

A craft designed to land on an airless body is very different from one designed to fly through the atmosphere. A lander can't escape Kerbin's atmosphere, while an orbital rocket alone is not designed to reach other planetary bodies. The open-ended nature of the game (a whole solar system to explore) leads to wild divergence for what constitutes success.

I began to see companies in the same way: because there are so many different ways in which to excel, and it's impossible for a company to excel at everything, successful companies are those which are most precisely adapted for their particular market situation in a way which allows them to use their unique strengths build enduring competitive advantage. Company designs can differ, but as long as all of their component parts contribute to success within their particular position and market, then they can be successful in different ways.

Another metaphor for this idea might be adaptation of animal species to particular niches in an ecosystem through the process of evolution. However I prefer the metaphor of vehicle design because it suggests purposeful activity rather than gradual and random change. Strategy is an active process.

Therefore, the practice of strategy lies in correctly understanding what is required for your particular company to successfully exploit the unique opportunities available to you, and configuring in a way that is optimized to achieve that success, and then executing consistently.

In other words, a successful strategy includes all of these elements:

- A theory about how to be successful

- A plan to put the theory into action

- An organizational configuration that supports the plan

- Consistent and excellent execution

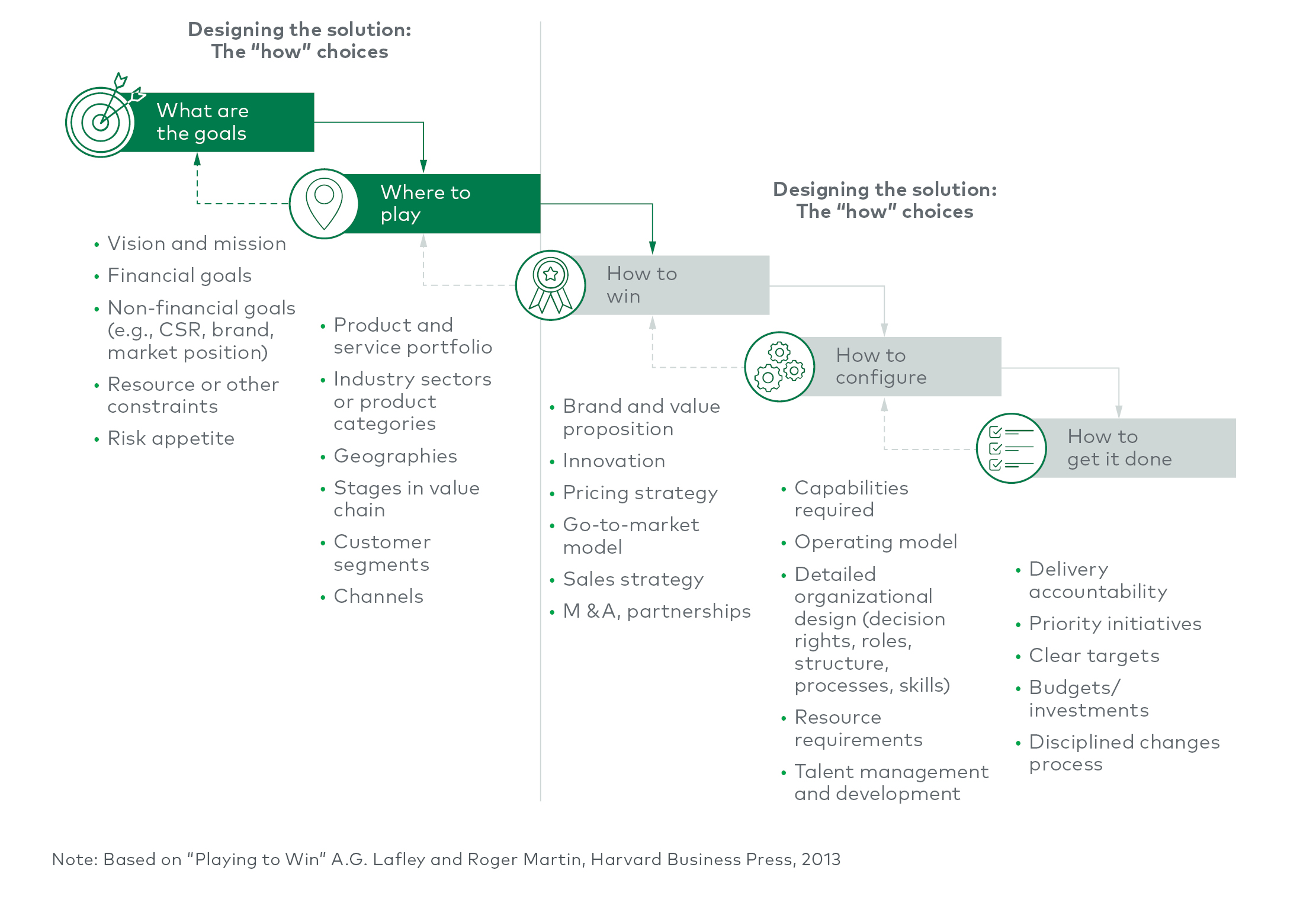

At global management consulting firms, the strategy process looks something like this:

At a big company working with a consulting firm, the strategy discovery and planning process might take several months and require a team of consultants. However, there's no reason why small businesses and startups can't run a stripped-down "lean" version of this process.

In future posts, I'll explore exactly how we at Blackpowder Advisory help small and startup companies run their own strategy process.