America Is A Commercial Republic

I wanted to write a follow up to last week's July 4th piece. The main idea I am exploring this July is that America's deep history shows a favorability and orientation towards business that is much more fundamental than most modern readers would appreciate. I believe that knowing this history can help us understand what it means to "be an American," and what American liberty is fundamentally for, especially in this historical moment when so many of us in the start-up world are concerned with rebuilding our nation's industrial capacity.

In last week's piece we examined how the Virginia Company, a for-profit enterprise, established the first English colony in North America. This venture featured a governance framework encoded in a corporate charter document, the accumulation of capital from thousands of investors, provision for representative government, and and arduous, risky work by colonists who eventually succeeded in building a successful and uniquely American society as the fruit of their efforts. All of the forms of governance and the elements of the American national character were present in the Virginia (and Massachusetts) prototype forms.

In this week's piece I'd like to touch on some of the particular developments in Federal and local state corporate law that shaped the development of the early American business environment. Through these explorations we can better understand the attitudes of early American thinkers and business leaders as they grappled with the challenges of managing and growing a burgeoning American economy. My primary reference here is the book "We The Corporations" by Adam Winkler which I highly recommend.

The Constitution As Corporate Charter

Before the Revolution, Americans referred to their "charter rights" in the same way we would refer to our constitutional rights today. Virginia, Massachusetts, and many other colonies were not founded not as feudal land grants, but as corporate enterprises through the issuance of Royal charter documents. These charters featured provisions for self-governance, a chief executive, a representative legislative body, and many even featured explicit bills of rights. In the decades leading up to the Revolution, all of these charters were suspended and replaced with direct rule by English appointed governors. This was a source of enormous dissatisfaction for the colonists and a direct cause for the desire for independence. In the colonists' view, one shaped by a long tradition of English legalism, the King and Parliament had breached their long-standing contracts. According to the English government, corporations existed at the pleasure of the State and could be dissolved when they no longer served the interest of the Realm. Ultimately the question was settled by the War for Independence, and after the Declaration each State was re-founded using constitutional forms that strongly echoed their previous charters. When the Federal Constitution was written, it was formed as a contract between people and government. It featured a national Executive, a representative legislative body, and a Bill of Rights.

When we view the Revolution as a struggle to assert corporate rights against state interference, it becomes obvious how the independence of the corporate form in general became part of the fundamental logic of the early United States.

Protection of Corporate Charters From Interference by the State

Indeed, the question of whether corporations could operate without government interference was resolved through a series of Supreme Court decisions in the immediate decades following the Revolution:

In Bank of the United States v. Deveaux (1809), an important case developing the idea of corporate personhood, the Court ruled that corporations, like any other citizen of the United States, had the right to sue in Federal Court.

In Dartmouth College vs. Wooster (1819), the Court ruled that a corporate charter is a contract protected by the Constitution’s Contract Clause, preventing New Hampshire from altering Dartmouth’s charter and affirming the autonomy of private corporations from state interference. Importantly, the ruling opened the idea that corporations are free to pursue private interests and don't necessarily need to serve the interests of the state, a decisive break with English common law.

In Bank of Augusta vs. Earle (1839), the Supreme Court ruled that corporations have the right to do business across state lines unless explicitly prohibited by a state’s laws, establishing the principle of corporate “comity” among states.

All of these rulings had immediate and beneficial effect. Free from the fear of arbitrary government interference, Americans invested in new enterprises with greater confidence. Their new companies could operate across state lines, and had the right access impartial courts. They formed new ventures at enthusiastic scale. America, newly independent from England, had now liberated its businesses too:

"In the years after the Constitution was ratified, the founding generation, liberated from English control, enthusiastically embraced the corporate form. Joseph Stancliffe Davis, the Stanford historian who discovered there were only a handful of corporations formed in the decade prior to the Constitutional Convention, found over three hundred business corporations chartered in the United States in the decade following ratification of the Constitution. It was a spurt of corporate growth without precedent. Americans formed corporations to produce silk, cotton, iron, and maps; to construct aqueducts, dig mines, and run waterworks; and to operate ferries, banks, and insurance companies. Most of all, corporations were created to build the scores of turnpikes, bridges, and canals that began to stitch together the independent colonies into one nation with a single, national economy."

(WTC Ch. 2)

The Democratization Of Corporate Formation

Since the days of the Romans, corporate formation had always been the closely supervised purview of the sovereign. The English kings continued this tradition; corporations, with potential to accumulate wealth, and special status as immortal persons, could only be formed by a royal act.

In the early United States, corporate formation was at first similarly subject to an act of legislature on a case-by-case basis, which invariably entangled the process of corporate formation with politics. Corporations were often subject to strict limits, with caps on how much capital they could raise, or periodic expiration of their charters. However, with growing demand for business growth, formation rules rapidly liberalized.

New York was the first state to offer corporate formation as an administrative procedure with the General Incorporation Act of 1811, which allowed manufacturing firms to form without needing legislative approval. Other states soon followed. Now even joint-stock corporations could be formed with ease and capital could be raised at a speed and scale unmatched anywhere in the world. The growth of the stock market indicates the enthusiasm with which Americans formed new ventures. In 1830 there were days where fewer than 50 shares were traded on the New York Stock Exchange. In 1861, just before the outbreak of the Civil War, the NYSE was regularly trading tens of thousands of shares per day. Compare this with England, which saw most of its industrial ventures formed under partnerships due to lingering suspicion of joint-stock corporations after the boom-and-bust cycles of the East India and other English stock corporations in the 18th century, and which thus tended to experience more frictions raising capital than their American counterparts.

At the same time that business formation rules were liberalizing, populist politicians and judges began cutting back monopolies. While the earlier conception of corporations approved by legislatures had carried an implicit understanding that their charters granted rights to operate monopolies (for example in the case of a toll bridge or a state bank), the ascendant Jacksonian class of the 1830s believed strongly in competition and democratic access to the corporate vehicle. During these years the Supreme Court consistently upheld the rights of new entrants to operate in previously monopolized markets.

Low Corporate Tax Rates

For most of the 19th century, American corporations paid no income tax whatsoever. Companies might pay excise fees for the right to do business in certain states, or pay property tax on land holdings, but taxes on corporate profits did not become common in the United States until the 20th century. Short lived attempts to impose a federal corporate income tax were shot down as unconstitutional in 1861 and again 1894. As a result, early American businesses were able to enjoy their profits and were free from the regulatory burden associated with filing taxes. Far from a fringe libertarian ideal, the principle that businesses should generally be free to pursue their growth and interests without being hindered by government was a widely held belief.

The Nascent American Colossus

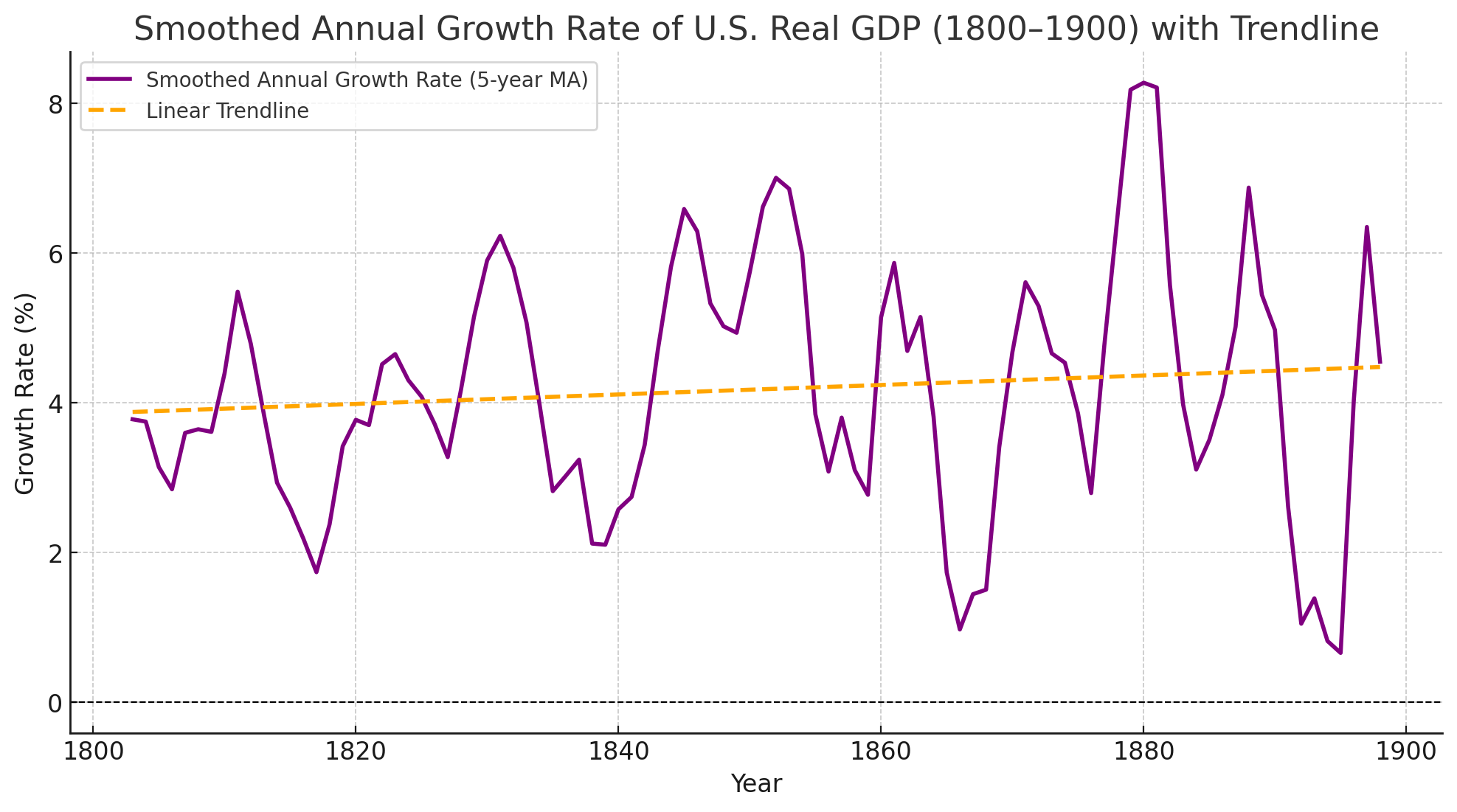

Early American favorability towards business was more than a set of policies. It was a manifestation of hard-won national character that was expressed in law, multitudinous individual enterprises, and national policy. The result of this uniquely American entrepreneurial culture was an astonishing profusion of new businesses launched in the 19th C. Banks, railroads, telegraph companies, insurance companies, mines, manufacturers, timber, tobacco, textiles, whaling, and long distance ocean trade: all of these flourished. As the fledgling United States grew in population and industrialized, the decades from 1850 - 1880 saw yearly GDP growth averages of 4% per year.

At the time, these were the highest economic growth rates in the world. The United States outperformed on a per-capita basis as well, reflecting general efficiencies in the American economy. Coupled with a rapidly growing native population, the 19th century and its liberal business climate set the stage for America's ascendance as an economic giant and eventual world power in the 20th century.